I’ve got a piece up today at Huffington Post Books that talks about the process of creating our comic book documentary on the Warren Report…and about why I don’t call it a “graphic novel.”

I’ve got a piece up today at Huffington Post Books that talks about the process of creating our comic book documentary on the Warren Report…and about why I don’t call it a “graphic novel.”

Several pages of excerpts are included.

Check it out here.

I’ve got a piece up today at Huffington Post Books that talks about the process of creating our comic book documentary on the Warren Report…and about why I don’t call it a “graphic novel.”

I’ve got a piece up today at Huffington Post Books that talks about the process of creating our comic book documentary on the Warren Report…and about why I don’t call it a “graphic novel.”

Several pages of excerpts are included.

Check it out here.

Filed under Uncategorized

I’m heading east for New York Comic Con, which runs from October 9–12, and together with Jerzy Drozd, I’ll be participating on a couple of panels and signing copies of our new documentary comic book, The Warren Commission Report: A Graphic Investigation Into the Kennedy Assassination. We’ll also talk about the work of our nonprofit organization Kids Read Comics.

I’m heading east for New York Comic Con, which runs from October 9–12, and together with Jerzy Drozd, I’ll be participating on a couple of panels and signing copies of our new documentary comic book, The Warren Commission Report: A Graphic Investigation Into the Kennedy Assassination. We’ll also talk about the work of our nonprofit organization Kids Read Comics.

Here’s the schedule:

Thursday, October 9, 7pm: NYCC Kickoff Party at Bergen Street Comics! – Ernie Colón joins Jerzy and me, plus some other great cartoonists, for an evening of fun (and book signing) at Brooklyn’s Bergen Street Comics. Details here.

Friday, October 10, 11:15 am: Abrams ComicArts Preview Panel, NYCC 1A01

For 65 years Abrams has been the country’s premiere art book publisher. It’s been five years since the launch of Abrams ComicArts in 2009, and the tradition of excellence continues with bestselling, award-winning original graphic novels and coffee table books. Join the ComicArts team and their Authors as they discuss current titles, and reveal exciting details about the upcoming Spring 2015 list and forthcoming projects. Includes a slide show, surprise announcements, special guests and giveaways.

Friday, October 10, 2:15 pm: Library-Based Comic Conventions Panel, NYCC 1A01

The future of libraries and the future of comics are converging: not only through ever-growing graphic novel sections, but through comics-focused programming, particularly programs aimed at youth and teen patrons. Libraries now host full-fledged comic book conventions that have drawn hundreds, sometimes thousands of attendees, as well as popular comics creators as guests.

Both panels will be followed by book signing at the Abrams booth, #2228.

Hope to see you there!

Filed under Uncategorized

Here’s the full text of the interview I did with Esquire.com, from which selections were taken to accompany the article and book excerpt they published about the Warren Report comic book documentary:

Let me answer with the general before the specific. When Ernie Colón was interviewed about his work on the comics adaptation of the 9/11 Report, he was asked about the risk of oversimplifying a complex topic, and his answer has almost become a mantra for me: When we do comics, we’re in the business of clarifying.

The distinction between simplifying and clarifying is hugely important. Comics have a great capacity to bring light and understanding in a way that dense prose can’t always do—and it’s hard to get denser than the Warren Report. Images have the power to fix important details in the readers’ minds and allow them to see the relationships between those details more clearly. When the facts are in dispute, as they are in the case of the Kennedy assassination and the findings of the official investigation, being able to hold on to that clarity and those relationships is even more crucial.

Comics also have the wonderful quality of letting us move seamlessly through time and space and from one point of view to another, which helped us a great deal, because any review of the Warren Report needs to cover a wide range of locations and viewpoints.

Except in the extreme and unlikely case where someone might call a 20-page superhero comic a “novel,” there’s probably no difference at all. But there are a couple of reasons I’m not comfortable with the term “graphic novel”: it can be wrongly understood to refer to fiction alone or to content that’s “graphic” in the sexual sense; and in grasping after the respectability of the “novel,” it seems to me to overemphasize text and underplay the importance of visual storytelling.

On the other hand, one cartoonist friend responded to my rant on this topic by saying that when he made comics he was poor, but when he started doing graphic novels he got paid. If it must be done, I can’t think of a more valid reason to change the name.

But I’m happy to describe The Warren Commission Report as a comic book documentary.

Looking back, I think I was startlingly overconfident about how easily all the pieces would come together. The challenges weren’t so much in determining the broad sweep of what would be covered as in figuring out how deep into the weeds we needed to get. When was it enough to lay out the basics of a particular dispute over the evidence—showing an event as it would have appeared under one interpretation and then under the other—and when did we need to really delve into the argumentation, which would require finding oral testimony so we could show a person talking (in order to make the narrative as “comic book-y” as possible)? And when do we put an end to the otherwise endless theorizing? Is it absolutely necessary to give credence to the people who think that Jacqueline Kennedy had her husband murdered?

Even when we pared things down to what must be told and what can be implied or set aside, I had to rely on all my experience using the techniques of visual storytelling through comics (because a writer of comics who doesn’t draw them still needs to think visually and find the best ways to convey the information). But here’s where Ernie’s experience in nonfiction comics was so incredibly valuable. Starting with The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation, he’s honed a particular narrative style that I was able to learn from and collaborate on. Ernie has committed himself to being a good reporter: witnessing without intruding; staying clear of attention-grabbing perspectives and angles that might overdramatize a scene that ought to be allowed to speak for itself. His art very literally stays on the level.

That approach forced me to be an honest broker of the facts…not that that wasn’t my intention to begin with. An odd thing about comics is that the medium is full of constraints—the size of the page, the amount of visual information it can contain, the limited space available for text—but learning to work within those constraints can be liberating; it focuses you on what can be done and what must be done. Here, Ernie’s reportorial style placed limits on what I could do, but kept me securely on the right path.

Ernie said to me one time that once we have enough experience making comics, we can throw off our constraints and apply our disciplines; and of course, “constraint” and “discipline” come close to describing the very same thing, the difference being intention. With the application of discipline, there was always a means of finding the core of what we were reporting, no matter how complicated, and rendering it visually.

One of my favorite sequences in our book features two double-page spreads that are laid out very similarly, and in fact contain some identical images, but which represent very different understandings of the assassination. Both spreads cover the few seconds after the shots are fired, but the first shows witnesses who believed they heard shots or saw a gunman at the Texas School Book Depository, while the second focuses on those who were certain the shots came from the notorious grassy knoll. In so strongly echoing each other visually while telling opposing narratives, these pages demonstrate how close the two “alternate realities” are to each other, how easy it would be to find yourself a resident of either one, and how radically your understanding of the whole event is altered depending on which side of the veil you stand on.

One way or another, that’s a strategy we deploy many times—replaying a scene with greater depth or from a different point of view, but calling back visual cues or aural ones (like the sound effect of a rifle shot) to remind readers that what they’re seeing is both different and the same. And that goes to one of the key things we wanted to accomplish with the book, which was not only to indicate what the Warren Report said and what the report’s critics have said, but how and why the argument has persisted for half a century.

I was also very pleased that one gamble we took paid off in a big way. This grew out of a central narrative dilemma: It wouldn’t be very illuminating to the readers if we showed the events of the assassination—a confusing jumble of sights and sounds experienced from a variety of perspectives over the course of just a few seconds—and then didn’t try to make sense of those events. On the other hand, we didn’t want, and comics don’t support very well, endless captions full of longwinded explanation; anyone who wants longwinded can just go to the original Warren Report. So what we did instead was collapse the time between November 22, 1963 and the time that witnesses and participants gave testimony or had conversations or wrote diary entries about that day, and we turned that testimony into word balloons. For example, when we show Secret Service agent Clint Hill pushing Mrs. Kennedy back into the limo, he tells us in a couple of balloons what he saw and what he believed it meant.

We were a little concerned that readers would struggle with this combination of present action and future recollection if we weren’t careful with how we presented it. But I think it worked out very well, and that readers will benefit from the way we used the unique qualities of comics to bridge the gap between event and interpretation.

Besides staying awake while reading it?

I’m only half joking: the original report is dense, dry, and anything but transparent. The writers also seem to have adopted the strategy that piling on words, whether they’re particularly relevant or not, would make the effort seem more authoritative. We couldn’t let ourselves fall into that trap.

More seriously, it was tough to figure out how to handle the gory parts that are at the center of this whole story. When does a graphic medium become too graphic? Even though I had to look again and again at frame 313 of the Zapruder film, the one that shows blood and brain matter exploding from the president’s skull, did I want to subject the readers to that? Ernie—as a visual thinker—argued in favor of more gore, for not shying away from the violent reality; so there are a couple of pages where that’s more in evidence than I was initially comfortable with, though it falls well short of shocking or grotesque. I think that’s a good thing.

Beyond that, there was the challenge we always face in comics: how to find for each panel the single image that can stand as the representative of all the others we’re not showing, a task made more difficult in a story so dependent on split-second timing, the precise location of bodies, and minute differences in the interpretation of physical evidence.

We were also tested somewhat by a section of the book that doesn’t directly reflect what’s in the report at all. Although our book is emphatically not about presenting our own whodunit theory of the case, it does level some serious criticisms at the Warren Commission, which, even if one argues that they did get the main facts right, made serious and consequential mistakes that have haunted the last fifty years of American history. In an email with my editor, I could state the cultural-political-historical case for the commission’s failings pretty succinctly; but turning a political science critique into a visual narrative did not come easily.

A part of me wants to escape back to the fantasy adventures I built most of my career on—and where, as a I like to say, the only thing that has to be true is the characters’ emotions—but I also feel like I’ve been bitten by the nonfiction bug. I’m already well into the research for a project that deals with the space program and the Apollo missions; and I’ve been mulling over how I might approach the eventful year of 1968, perhaps through the personal stories of everyday people as well as those who made headlines.

And after that, maybe I can finally be done with the 1960s.

The major goals of our book are to show how the different interpretations of the events surrounding Kennedy’s death arose and why the disagreements about the facts persist; to illuminate the times in which the assassination occurred and which were the context for compiling the official narrative; and to explore the influence of the Warren Report on the years and decades that followed. Whether we lived through those times or not, we’re all living with the consequences of how the Warren Commission conducted itself.

Filed under Uncategorized

A couple of weeks ago I got tagged on Facebook to “name 10 books that have stayed with you in some way.” “Don’t take more than a few minutes,” the instructions read, “and do not think too hard.”

Here’s why I’ve delayed responding: Books that I’ve read are always popping into my head, and I hardly have to think at all (let alone “hard”) before the memory of one book leads to an association with another (or several others), and the chain gets pretty long pretty fast if I don’t put the brakes on. They expect me to shut up after only ten books? Do my Facebook friends know me at all?

But let’s have a go—onward and associatively—and see where we end up.

Catch-22 is the obvious place to start. I reference the opening lines, and Clevenger’s trial, and the soldier in white, and the soldier who saw everything twice, and the character who was an old man when he died at age 19, and plenty of bits of Yossarian’s dialogue (in French even: “Ou sont les neigedens d’antan?”) on a fairly regular basis. That’s some catch, that catch-22. (“It’s the best there is.”)

Catch-22 is the obvious place to start. I reference the opening lines, and Clevenger’s trial, and the soldier in white, and the soldier who saw everything twice, and the character who was an old man when he died at age 19, and plenty of bits of Yossarian’s dialogue (in French even: “Ou sont les neigedens d’antan?”) on a fairly regular basis. That’s some catch, that catch-22. (“It’s the best there is.”)

And now I’m off on other war stories: Tim O’Brien’s classics, Going After Cacciato and The Things They Carried; Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five; Bobbie Ann Mason’s In Country and Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (the last two much more about homefront America than the wars they meditate on).

Set aside science fiction wars, though I’m sure a much younger me would have had Starship Troopers on the list; but don’t abandon science fiction: Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End, and his short story “The Nine Billion Names of God,” two different takes on some big questions about human existence. (I’ll digress to mention one more short story by a genre writer, “[X] Yes” by Thomas M. Disch, which is most haunting for the details it leaves out; and actually, a month doesn’t go by that I don’t mention Disch’s novel Echo Round His Bones and its very disturbing premise.) And then Philip K. Dick’s various takes on the big questions, in novels like Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (probably my favorite of his books and, strangely, still not a movie); not to mention his twisty take on alternative history, The Man in the High Castle, with its doubly altered outcome for World War II. (I see now that the Library of America is on my wavelength, having collected those three novels, plus the delightfully trippy Ubik, into a single volume.)

And I do love that alternative history: Keith Roberts’ Pavane (the Spanish Armada restores Catholicism to England), Ward Moore’s Bring the Jubilee (the south wins the Civil War). And thinking of the era of great postwar SF, I’m always recommending George Stewart’s Earth Abides, the first great “ecology science fiction” novel; and then there’s the psychological acuity of Algis Budrys’s Rogue Moon and Who?, which makes me think about Stanislaw Lem’s Fiasco.

But I almost lost the thread of big questions, in particular religious ones, something I ought not do without mentioning Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow and James Morrow’s Towing Jehovah (which I describe as Moby Dick meets God is dead).

Religious non-fiction sticks with me too, with Karen Armstrong’s book about the Axial Age, The Great Transformation, and Stephen Prothero’s God Is Not One, which challenges the easy truism that all religions are aiming at the same ultimate ideas, and which maybe gets an unintended response in Sandy Eisenberg Sasso’s splendid children’s picture book In God’s Name, beautifully illustrated by Phoebe Stone. (And I can’t bring up any children’s books without pausing to extoll Jerry Spinelli’s Maniac Magee.)

Big questions get a memorable workout in Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcyle Maintenance, and the admonition the narrator directs at himself on the final page (“Be one person!”) shakes me up every time I think about it (and makes me think of the story of Rabbi Zusya on his deathbed, though that connection may indicate that what I took from the line is different from what Pirsig meant by it).

Around the time I read Zen and the Art, I also read a book called The Unchanging Arts, which really changed my sense of how to think and talk about art—not in terms of whether something qualifies as being art, but in terms of what art does.

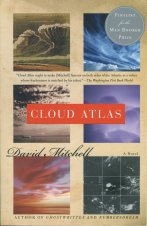

The time I read those books would have been the mid- to late 70s, and now I realize that only three of the books I’ve mentioned so far were published in the current century. Coming up to speed, there’s Cloud Atlas (which probably would have shown up as #2 after Catch-22 if I’d been ranking these as favorites); I can’t forget David Mitchell’s follow-up novels either—Black Swan Green and The Thousand Autumns of Jacob DeZoet (and though I think his new one, The Bone Clocks, has some serious flaws, I’m pretty sure its main character will stay with me for a long time).

The time I read those books would have been the mid- to late 70s, and now I realize that only three of the books I’ve mentioned so far were published in the current century. Coming up to speed, there’s Cloud Atlas (which probably would have shown up as #2 after Catch-22 if I’d been ranking these as favorites); I can’t forget David Mitchell’s follow-up novels either—Black Swan Green and The Thousand Autumns of Jacob DeZoet (and though I think his new one, The Bone Clocks, has some serious flaws, I’m pretty sure its main character will stay with me for a long time).

Mitchell leads me into the whole realm of “good” books–good in the sense that the level of the writing is high and the concerns of the author are important, and also good by virtue of brimming with story (maybe “plot” is a better word) and characters that keep my full attention—like the aforementioned Moby Dick or (how could I have gone this long without bringing it up?) Huckleberry Finn. Put Robertson Davies high up on this list for me: his interrelated novels like the Deptford Trilogy (especially the first volume, Fifth Business) and the Cornish Trilogy, but also standalones like The Cunning Man. More recently, the Irish novelist Paul Murray’s Skippy Dies took its place in my personal canon of unforgettables, and boy, did I like a novel I read just a couple of weeks ago, Your Face in Mine by Jess Row—an indelible story about race that posits a way in which race might itself not be so indelible.

Great writing and great story and “written in the 21st century” come together in a couple of genre books I’ve been pressing on friends for the last few years: Nick Harkaway’s The Gone-Away World and China Miéville’s The City and the City, both of them mindbenders, and genre-benders too. Speaking of genre-busting (and going back to the 70s)…William Hjortsberg’s Falling Angel is a detective novel and occult novel rolled into one, and for the entire time I was reading it, I assumed it would have to “decide” to be one or the other, but it didn’t; it’s both.

OK, running out of quick, random associations—not out of books, but remember, I’m not supposed to be thinking too hard (and I’ll resist adding titles that come to mind even as I’m writing these words). So I’ll end with two comic books, and surprisingly, given the degree to which comics are a part of my life, it’s easy to stop with two that for me stand head and shoulders above the rest. One is the first comic I ever read, an issue of Sheldon Mayer’s Sugar & Spike. I don’t know which issue it was—hey, I was five years old—but Mayer was brilliant, and Sugar & Spike was brilliantly conceived and executed; it was just the thing to put in front of a susceptible child who, upon first exposure to what comics are and what they do, could intuit that this was something breathtakingly wonderful, and that the only response to reading one was to demand more.

The other comic is actually a reprint of stories that were then a couple of decades or more old. In 1966, Harvey Comics published a giant-sized (it cost a quarter) collection featuring some of Will Eisner’s greatest Spirit stories from the newspaper-insert comic he began in the early 40s. I’d never heard of Eisner or The Spirit before then; there was nothing on the cover to indicate that these stories were classics or exemplars of the best of what comics can do. But the latter fact was easy to discern, and these relics (in both senses, that of being ancient and that of possessing an almost sacred quality that made them worthy of veneration) awakened me with the force of revelation.

Over the years, I’ve bought plenty of Eisner’s books, many in beautiful hardcover packages. But when I met the man himself at a Motor City Con in the 90s where we were both guests, and I could choose any one of those books for him to sign (the con was close enough to home to drive there each day), there was only one I wanted his autograph on: my battered, beloved, 30-year old copy of Harvey Comics’ The Spirit #1.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have books to read.

Filed under Uncategorized

The first mock-up of the cover for The Warren Commission Report: A Graphic Investigation into the Kennedy Assassination showed that the book was “by” me and “illustrated by” Ernie Colón and Jerzy Drozd. An ego boost for sure, but also a pretty insane way to describe the writers and artists of a comic book. I said as much to the folks at Abrams ComicArts, our publisher, and they quickly rectified the situation. The credit line now just lists our three names.

The first mock-up of the cover for The Warren Commission Report: A Graphic Investigation into the Kennedy Assassination showed that the book was “by” me and “illustrated by” Ernie Colón and Jerzy Drozd. An ego boost for sure, but also a pretty insane way to describe the writers and artists of a comic book. I said as much to the folks at Abrams ComicArts, our publisher, and they quickly rectified the situation. The credit line now just lists our three names.

My objection to the original credits is twofold: the idea that I’m the true author, the possessor of the singular vision that carried the work through from conception to completion; and the description of what comic book artists do as “illustration.” Unless one person really is doing it all, making comics is a collaborative effort; and the people who draw them are not illustrators—certainly not in the sense that they provide adornment for a finished text, or even that the pictures they create explain or clarify some aspect of that text. With no slight intended toward artists of children’s picture books or those who do spot illustrations for novels (many of whose names will be lauded long after mine is forgotten), what comic book artists do is something different.

That is, comic book art is not an aid to understanding the narrative; it is central to it. It is the thing itself. Because without the drawings, there’s really no narrative at all—at best, there’s a sketchy and frustratingly incomplete blueprint for one. The visual thinking—the visual storytelling thinking—that artists bring to a project is essential to making the narrative work, and writers ignore or reject it at their peril.

Even in a book like The Warren Commission Report—which began with a huge amount of content that had to be considered, selected and organized, and where that selection process was almost entirely in my hands—it was essential for me to be open and responsive to the artists at work.

For one thing, Ernie now has a long track record in nonfiction comics, starting with The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation in 2006; and in that book he devised a particular reportorial visual style that I needed to understand and internalize (as did Jerzy) in order for us to work effectively as a team. That style plays a crucial role in establishing the fairness and objectivity of the narrative, and I could not have conceived of it myself.

On the other hand, to portray me as “author,” and Ernie and Jerzy as “illustrators,” rather underplays my role in the finished art, even while overstating the mighty force of my guiding intellect. I thought long and hard about what each page would look like, drawing on more than thirty years of comic book writing experience to find the best and most apt techniques of visual storytelling to use. Not just the basics, like making sure I didn’t clutter the page—though Ernie will correctly say the early drafts didn’t always succeed at that—but choices related to compressing or expanding the action; what image should dominate a page; appropriate balloon placement (a visual element just as much as it’s a textual one); and the use of color to provide cues about both factual and emotion content.

The truth is, as anyone who has worked in comics will tell you, readers regularly praise or pan an artist for something the writer bears greater responsibility for, and vice versa.

And yet, when I look at comic book reviews in places like The New York Times, what I see is that old formulation: “by Writer X, illustrated by Artist Y.”

Of course you don’t have to tell me that the “illustrator” credit has plenty of history in comics, used liberally when credits started to appear in monthly titles, especially at Marvel. I suspect, though, that the term was at that time meant to elevate the presumed hack scribbler working in a gutter medium. “Illustrator” sure sounds important.

But it’s the wrong word. And to use it now, I think, perpetuates a pernicious misunderstanding of what the people who draw and write comics actually do. If a rough distinction has to be made regarding who did what, I’d say that “written by” and “drawn by” are much closer to the mark—it’s the “drawn-ness” of comics that makes their narratives unique, after all.

What I know for certain is that a story told in comics is told collaboratively, by everyone whose name is in the credits, not “authored” by one and then “illustrated” by another.

Filed under Uncategorized

A rumor that recently hit the Internet suggested there might be a new back story for the Wonder Woman who’ll show up in the next Superman movie: that the Amazons she belongs to are descended from the Kryptonians–the ancient spacefarers who, according to Man of Steel, tried to set up outposts of their civilization on various worlds millennia ago.

A rumor that recently hit the Internet suggested there might be a new back story for the Wonder Woman who’ll show up in the next Superman movie: that the Amazons she belongs to are descended from the Kryptonians–the ancient spacefarers who, according to Man of Steel, tried to set up outposts of their civilization on various worlds millennia ago.

Turns out this started with idle chat from someone unconnected to the movie, whose guesses are about as good as yours or mine. But after reading the goggle-eyed, hair-on-fire, head-exploding reactions that the original rumor ignited, I really have to ask:

Why shouldn’t Wonder Woman be a Kryptonian?

Among the many dreadful, stupid reboots and retcons that have shown up in superhero comics and in their film and television incarnations, this isn’t half bad. It’s certainly better than what I heard from a TV producer whose interest in Amethyst, Princess of Gemworld, boiled down to removing every aspect of the character that made her interesting and unique: no kid-to-adult transformation, no Gemworld to be seen, no demonstration of magic that couldn’t have been done with the special effects on Bewitched.

To react as if an alien background for Wonder Woman and the Amazons constitutes a travesty against a received, canonical version that never has been and never should be violated seems a bit of a reach. True, the story of the Amazons of Paradise Island has probably stayed more consistent than the history of Krypton and its culture…but I suspect that has mostly to do with Wonder Woman’s being an undeveloped backwater, an afterthought to many editors, writers and fans, not to mention Hollywood studios. But the changes she’s undergone over the years have still been substantial.

Paradise Island went from being a kind of year-round, single-sex summer camp to being Themiscyra, the home of an ancient warrior people. (I think I was the first writer to refer to the mythological name, during my run on Wonder Woman in the early eighties; I’d also say I placed the Amazons about midway between the frolicking peaceniks and the Klingon wannabes that mark the ends of the spectrum.) Such consistent themes as could be found involved an emphasis on finding the better angels of human nature, along with healing (the purple ray) and truth (the magic lasso, though let’s not go into the relationship between truth and bondage right now). But exactly what deeper values were being expressed was pretty subject to interpretation. Amazon ideas about the meaning of love, for instance, are hard to pin down. Steve Trevor has gone from dreamboat to dead to undesirable, and never enjoyed the iconic status of Lois Lane.

You also don’t hear a lot these days about Princess Diana’s having been fashioned out of clay by her mother. And I hope it’s no longer the case that she became the Amazon’s representative to the outside world by winning a competition that was far from fair, since the gods gave Diana special powers no other Amazon possessed on the day she was not quite born.

As for those powers, some commenters on the new origin rumor speculated that although of Kryptonian heritage, Wonder Woman wouldn’t be as powerful as Superman–owing to the Amazons’ acclimation to Earth over time–and were pretty cheesed by that diminishment. Say what you will, though, about whether Wonder Woman should be presented as Superman’s equal in strength, it’s a fairly recent notion that she even could be. Her gods-given gifts never approached the level that Superman’s powers have been set at since at least the 1950s. She had to fend off bullets with her bracelets, not with impenetrable skin; and back when I wrote the character, she could not fly, just glide on air currents, which is why the invisible robot plane came in handy. (Contriving to put her in a place where she could catch those air currents, by the way, was an all-around pain.)

I’ll save for another day a lengthy discussion of the major flaw I saw in Wonder Woman after three years of writing her adventures–that she was set up to preach a message more than she learned and lived it–or about the proposal I made to have her disappear in Crisis on Infinite Earths and be replaced by a flawed, mortal woman who would gain the powers and only slowly discover where they came from. But in some ways that would not have been a much greater change than the ones made in Superman around the same time, including the replacement of Krypton the lost and mourned world with Krypton the sterile and cerebral culture that, let’s be honest, deserved to die.

And now there’s the Krypton of Man of Steel, which I was kind of taken with, even though my heart belongs to the vanished paradise drawn by Wayne Boring and Curt Swan. That the Amazons could be an offshoot of that Krypton strikes me as pretty clever. It would forge additional connections among the characters of the DC Movie Universe (a tactic that’s worked well with the Marvel movies), and could lead to nice visual notes like having the Amazons’ technology mimic that of MoS’s Krypton.

And to those who say that a Kryptonian origin would mean chucking any connection with the Greek gods, I ask why so? If the Amazons have been here long enough, they would have had plenty of opportunities to tangle with those gods, and would have presented a more challenging obstacle to them than mere human beings did. If the Amazons then decided to stick with a look and culture influenced by their Achaean neighbors after settling down on whatever they call that island, who am I to argue with them?

***

Of course, it is always possible to bend a character so far she breaks apart from any recognizable version of herself. But that’s Amy (Amethyst) Winston as a 25-year-old office worker in L.A. who wiggles her nose to make things levitate, not Wonder Woman having a surprise connection to Superman in the far distant past.

Ultimately, what’s most important in these matters is finding a way to keep true to the core, the essence, the reason a character exists in the first place. And unfortunately, the second biggest obstacle to making a successful Wonder Woman movie (we all know what the biggest one is) is that so few people can articulate what Wonder Woman’s reason for being really is, and that among those who think they can, there’s a pretty wide range of opinions.

So give me the one-sentence description of Wonder Woman–heck, you can even have one short paragraph–that people can rally around, that shows why she’s unique, and that’s likely to stand the test of time, and that’s when I’ll say, “Stop right there and don’t change a thing.”

Filed under Uncategorized

Today would have been the fifty-first birthday of Dwayne McDuffie, a colleague and friend I admired a great deal. Tomorrow will be two years since his death. Dwayne was among other things the creator of Static, a superhero I consider to be the best since Spider-Man. (Though I’ve been known to boast that Blue Devil, by Gary Cohn, Paris Cullins and me, deserves that honor, Dwayne knew what I really thought.)

Today would have been the fifty-first birthday of Dwayne McDuffie, a colleague and friend I admired a great deal. Tomorrow will be two years since his death. Dwayne was among other things the creator of Static, a superhero I consider to be the best since Spider-Man. (Though I’ve been known to boast that Blue Devil, by Gary Cohn, Paris Cullins and me, deserves that honor, Dwayne knew what I really thought.)

Dwayne was also a man who knew his own mind, sure of what he stood for and what he’d stand up for. That he found a way to turn out terrific superhero adventure stories that appealed to young people at a time when the comic book superhero had largely become the province of much older fans (though he wrote for that older audience too) was something I considered a small miracle.

Dwayne’s work at DC and Marvel, his co-founding of Milestone Media, and his successes at Cartoon Network are well-known. What I want to do here is take a moment to remember his kindness.

One year at Comic-Con in San Diego, Dwayne and I were talking and walking past the tables of small, independent comics creators, stopping now and then to see what new and unknown work was bubbling up from new and unknown artists and writers.

Like anyone, when I see a comic that looks worth reading, I’ll grab the book, reach for my wallet and ask how much it costs; but when someone knows my name and my work, they’ll sometimes tell me just to take it, no charge, perhaps describing it as a fair exchange for the reading pleasure I’ve provided them. Knowing that the marginal cost of a comic book is surely not the cover price, and that the profit from one sale was not going to make or break their weekend, what I normally did was accept the gift with thanks and move on.

On this occasion, luckily for me, it was Dwayne who found something that intrigued him first, and when he reached for his wallet, he got the same offer I was used to, and likely deserved it more. But he responded in a way I never had. “No, man,” he said, “you worked hard on this. How much is it?” He made them take the money, and he made them feel good about making comics. And since I don’t believe he counted mindreading among his many talents, he missed my acute but thankfully internal embarrassment.

Needless to say, I don’t take free comics from young creators anymore. They’ve worked hard on those books.

Filed under Uncategorized

I’m always happy to see non-comics news media cover comics in a serious and thoughtful way, so I was pleased to find this article on The New Republic’s website last week. The writer, Glen Weldon (whose Superman: The Unauthorized Biography I’m definitely looking forward to reading) does a good job of bringing to a general audience a story about how some classic superhero comics got made. Which is also the story of how great companies and characters rose and fell, and how the creators of those characters got consistently shafted to one degree or another.

The concern I have with telling this story in a brief overview like Weldon’s is that it can tend to be as reductionist as the “official history” it aims to refute. And I worry the pendulum has swung from an accepted wisdom that says Stan Lee created everything to one that says he created nothing.

That Lee made himself the face of Marvel (for ego-boosting reasons or smart business ones, or both) is undeniable, as is the fact that Jack Kirby in turn felt undervalued. And when Kirby later asserted his creative importance by saying things like “I wrote those stories,” that was undeniably true in some very important ways.

But the Lee and Kirby stories read very differently from the Kirby solo or Kirby-and-anyone-else stories. And that was because of Lee’s words, preposterously showy and high-octane as they were; what made Marvel Marvel was the synthesis of what each man brought. As a kid I was more attracted to the comparatively staid DC books, and was even a little put off by the Lee brand of constant showmanship. But when Weldon says that “what made readers rabid for Marvel’s ham-fisted stories had less to do with how they were told, and much more to do with how they were sold,” I think he goes too far: at least in the early days of the “Marvel age of comics,” the selling and the telling were pretty inseparable.

So who did “write that,” and what is comic book writing anyway? (I should say at this point that I don’t have a personal stake in the answer to the first question: the extent of my acquaintance with those involved is that I’ve been introduced to Stan Lee a couple of times at conventions, and got seated next to Jack Kirby at a dinner once; I also had my first story at DC Comics drawn by Steve Ditko, and worked with Don Heck for a couple of years on Wonder Woman, though our communication was mostly through an editor). My experience tells me that while it’s true, as Weldon says, that Lee’s definition of “writing” wouldn’t line up with the average person’s expectations, the average person doesn’t understand how any comics are written, and certainly not that there are many ways to write them.

One thing I can say for sure about making comics is that anyone who wasn’t involved in a particular comic’s creation has no idea who contributed what; in fact, it doesn’t take long before even the people who did create the comic can’t sort it out anymore.

One reason for that is an aspect of the business of comics that Weldon doesn’t touch on: not marketing, but publishing schedules. Relentless monthly deadlines, especially when scrupulously attended to as they were in the sixties, mean an endless churn of pages and, if you’re producing a lot of work (or trying to), a lot of anxiety. There’s really a lot less time to think about how you’re going to do it, or what your master plan should be, or even how you’re going to sell it (if, like Lee, you’re wearing both the writer and the editor hat); it’s mostly about getting the damn work out!

And if some of it seems to succeed, and to strike a chord, then wow–give yourself a quick pat on the back before looking at your calendar to see when the next plot or dialogue job is due; or sitting down with the very exciting pages an artist has turned in based on a brief story conference and trying to figure out how they fit with what went before and what the characters might be saying in such a situation, while appearing to grow and change (without actually doing so, because your readers really want the characters to remain the same month after month).

“Plot-style” comics writing starts to look like a kind of salvation. And the truth is that comics stories can originate in all sorts of ways and then come together almost miraculously.

Yes, it’s hard to believe all of Stan Lee’s stories about the beginnings of Marvel Comics. My guess is that in many cases he doesn’t even know anymore if they’re true. Which is not meant as a slam. He’s a storyteller, and he’ll tell the story that seems to work in the moment–which may just mean that he’s never stopped writing, however you want to define the term.

***

One additional note on the Lee/Kirby relationship: I highly recommend Michael Chabon’s short story “Citizen Conn,” published last year in The New Yorker (Feb. 13, 2012). It certainly doesn’t represent the “true story,” but it richly imagines what might be at the core of such a partnership. And it’s anything but reductionist.

Filed under Uncategorized

I heard the latest news about Amethyst, that the current DC Comics series she’s been starring in has been canceled, on Facebook. That’s where I always hear that a character I had a hand in creating will be showing up in a new comic or cartoon or as a toy or what have you. Which is not to say that DC has made a special point of keeping me out of the loop; there’s a long tradition of comic book publishers pretty much ignoring the artists and writers who invented their characters when those people are no longer doing work for them. And I’ve got it a lot better than many of my predecessors who created far more well-known heroes than Amethyst or Blue Devil: I have a contract with DC that specifies the royalties I’ll receive when my work is reprinted, adapted or licensed, and DC always pays.

I heard the latest news about Amethyst, that the current DC Comics series she’s been starring in has been canceled, on Facebook. That’s where I always hear that a character I had a hand in creating will be showing up in a new comic or cartoon or as a toy or what have you. Which is not to say that DC has made a special point of keeping me out of the loop; there’s a long tradition of comic book publishers pretty much ignoring the artists and writers who invented their characters when those people are no longer doing work for them. And I’ve got it a lot better than many of my predecessors who created far more well-known heroes than Amethyst or Blue Devil: I have a contract with DC that specifies the royalties I’ll receive when my work is reprinted, adapted or licensed, and DC always pays.

But that doesn’t mean it’s easy to see my characters (not that they’re “mine” in any legal sense) used in a way that seems to fundamentally misunderstand them. Or sometimes to understand them but decide to change them anyway, as appears to be the case with the recent Amethyst series: DC recognized they had a character who could be altered to appeal to the “Hunger Games” audience, and so they took a story about a thirteen-year-old girl with a loving family but a hidden and wondrous and dangerous heritage, and made it about a seventeen-year-old who’s been living a desperate and unhappy life on the run before she discovers those older dangers. (I couldn’t say whether the “wondrous” part can be found in this version, since I’m only going by what I’ve read about the series, not having bought the comics myself).

It’s an understandable approach on DC’s part, adapting what they already own for today’s market, even if it didn’t make me happy. But making me happy is actually not in the contract I signed with them.

In any case, the poster on Facebook who called my attention to the cancelation of the Amethyst comic was happy to see it go, and figured I must be too. Well, yes and no. On the one hand, it definitely didn’t represent the Amethyst I’d like the public to know; but on the other, it’s never a good thing to have your work canceled and the impression left that it’s not marketable. Thankfully, I’m not looking for employment in the world of DC and Marvel heroes these days, so I don’t have much concern that those companies will take away a lasting impression that my stuff doesn’t sell. In the big picture, in fact, it’s their stuff that doesn’t sell…not like it did in the 80s and 90s when the bulk of my work for DC (and some for Marvel and Malibu and others) was done. The “public” that knows the latest comics incarnation of Amethyst is a pretty small one, far smaller than the number of people who’ve seen the charming minute-long animated shorts now appearing on Cartoon Network (which definitely “gets” the original comic book series, though it necessarily skimps on a lot of the detail and nuance).

And I do feel bad for Christy Marx and Aaron Lopresti, the talented writer and artist who poured a lot of themselves into the current series and who I hope will find immediate work to replace it. Better yet, somebody should pay them both to work on projects of their own creation. That’s not the way the monthly comic book industry works, I know–Gary Cohn and I were hugely fortunate to have come into the business at a time when publishers, DC especially, were excited about trying new things–but I’d like to believe such a moment could come around again.

Filed under Uncategorized